A look behind the curtain at the complexities of funding for the School of Music and Dance at San Diego State University

By Angelica Wallingford

Dec. 10, 2018

Story Highlights:

- School of Music and Dance at San Diego State University has been overspending and growing its budget for at least the past four years.

- The funding for the School of Music and Dance and other schools at San Diego State is calculated by a Full-Time Equivalent Student equation (FTEs).

- Grants and funds from donors help the School combat costs of performances on and off campus.

SAN DIEGO – It’s not an uncommon scene. Students rushing past with their instruments in hand scurrying off to their next class or having an impromptu dance or jam session with their classmates outside. The sounds of the jazz scales and arpeggios echo throughout the halls and bleed onto the surrounding walkways as others set up for a concert at the iconic Smith Recital Hall or Don Powell Theater.

One would never guess with all this activity that San Diego State’s School of Music and Dance has been overspending for at least the last five years.

“It’s true that the School of Music has been overspending its budget and that amount has been growing over about the last four years or so,” former Associate Dean of the School of Music and Dance Donna Conaty said. “It’s reached a point where it’s of concern.”

Despite the overspending, the department has achieved a lot over the years, with its award-winning ensembles, festivals and local performances showcasing the student musician and dancers that roam the halls. More recently, the Jazz Ensemble, led by Bill Yeager, was invited to perform in Montenegro for “Jazz Appreciation Week” slated for April 2019, a first for the ensemble.

“I noticed things like when I was in high school, like we need new instruments or music stands,” Samuel Anderson, a City College music student said. “I don’t necessarily think about back end stuff unless it affects the bigger picture, like a class being unavailable.”

Band Director and Undergraduate Advisor for the School of Music Shannon Kitelinger was an undergrad at Indiana University of Pennsylvania in the 1990s. Much like the students of today he had no clue of all the behind the scenes work that went on with the budget but he did notice other things that he felt needed attention at the time.

“I wasn’t aware of things like well we can’t offer enough classes because I was able to take my classes,” Kitelinger said. “I was aware of little things like the marching band needs a second director or an assistant director and they’re not paying for that.”

When she was an undergrad at Fresno State University, graduate student Erika Gamez felt the same as Kitelinger and Anderson. As long as the classes she needed were available, she didn’t really pay funding that much attention.

“You can kind of just tune it out and you don’t have to really think about that sort of thing,” Gamez said.

However, as a graduate assistant conductor for the marching and concert band, Gamez said that it has given her a new perspective on funding and how it’s handled in a university setting.

“I really think that now I’m getting to understand the system and the administrative side of things mostly, I guess you could say the politics that have to do with that sort of thing,” Gamez said.

Justin Joyce, another graduate student in the School of Music and Dance, says that funding for the arts in general is a part of an outdated “industrial revolution” type of mindset.

“In that sense, arts are put at the bottom,” Joyce explained. “I think it’s because arts, in a general sense, it’s such a way of expression and creativity and it’s so hard to qualify what things are.”

Looking back on his undergrad days, Joyce said that he views funding the same way he’s always had, not through rose-colored glasses but with a sharp dose of reality that he’s learned over the years being involved behind the scenes at the School.

“If everyone could please everybody it would be awesome but the thing about that is that decisions have to be made and usually these decisions are made not by one person, they are made collectively and represented collectively, usually,” Joyce said. “You can’t please everybody.”

While most students taking classes in the School of Music and Dance are quick to notice issues dealing with the class schedule, Kitelinger said it’s the professors, faculty and staff that deal with money issues behind the scenes.

Charles Friedrichs, the former director of the School of Music and Dance, says the university doesn’t fund music instruction the same way it does a large lecture class due to one-on-one teaching situations.

“Let’s say, you’re getting percussion lessons, well, there’s one teacher and one student, as opposed to 150 (students) in a lecture,” Friedrichs said. “So, it’s not cost effective and we don’t really fit.”

For Friedrichs’ five-year reign as director, the school has operated while overspending despite higher enrollment and audition numbers, the introduction of two new degrees and hiring new faculty.

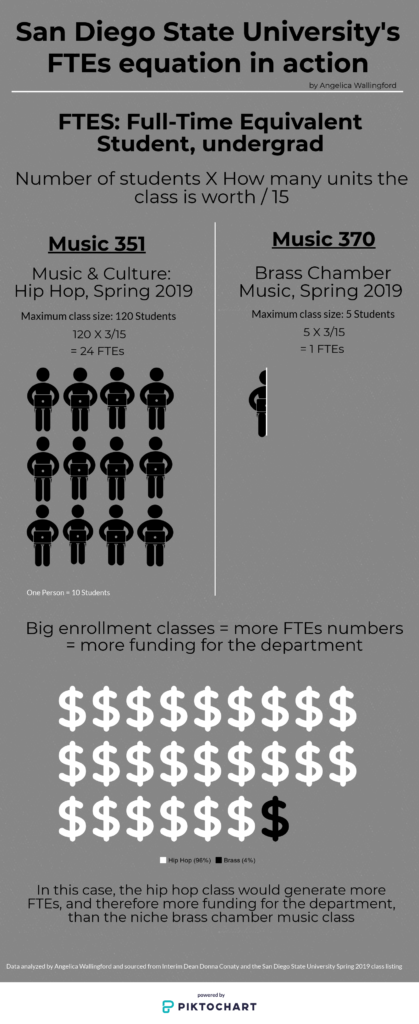

The “cost effective” measure that Friedrichs refers to is an equation used at universities throughout the United States called FTES, or a Full-Time Equivalent Student and according to Conaty, it’s an equation that is a make or break for the various departments at San Diego State.

IT’S IN THE NUMBERS

An FTES is defined as an undergraduate student taking 15 units and a graduate taking 12 units. A formula is used to calculate how much FTES a class generates and if a school goes above and beyond the quota it gets rewarded with more funding. This isn’t a new formula; it’s used at various campuses nationwide to calculate FTES for campuses that receive funding from its state, according to various university websites.

In the case of San Diego State, it’s a number set every semester for every college in the university usually by the dean, according to Conaty. If a school within a college meets their goal funding, it stays the same. If it falls short, funding is reduced however, if it exceeds, they get more.

“It’s an interesting model,” Kitelinger said. “Within the college we actually eat each other, we’re supposed to bring in students to fill their GE (general education) requirement…Great we got them, now they’re not going somewhere else within the college.”

This infographic shows a comparison between two classes, the higher capped Music and Culture: Hip Hop class and the more niche five-student capped Brass Chamber Music class. The hip hop class has significantly more students enrolled than the brass chamber music class and therefore will churn out more FTEs. The more FTEs a department gets overall, the more likely it is that they can receive more funding.

However, not every university in the U.S. uses the FTES model for funding. Scott Lipscomb, the new director for the School of Music and Dance, has worked in administration positions at the University of Minnesota and the College-Conservatory of Music at the University of Cincinnati. Both had very different models for dealing with funding.

At the University of Minnesota, Lipscomb said he dealt with a fairly typical funding model for most institutions which is “here’s your slice (of the pie), make it work.”

“The college basically said ‘we have X number of departments within our college and here’s the chunk for the School of Music…,’” Lipscomb said. “Basically, you were responsible for taking that slice of the pie and making sure whatever costs your department had fit within that maximum amount.”

The University of Cincinnati did things differently. It uses a system called Performance Based Budgeting or, as it’s also called, Responsibility Centered Management, in which the dean of the department would make decisions based on courses and enrollments that those courses generate, according to Lipscomb.

“In that capacity, each dean at the University of Cincinnati is responsible for generating sufficient income to cover the costs of instruction,” Lipscomb said. “So where that might work effectively for a business college or for an engineering department, that just doesn’t work for music and I would say for all the arts.”

Prior to Friedrichs taking over, Conaty ran the School of Music and Dance for six years before taking her position as associate dean and currently the interim dean for the College of Professional Studies and Fine Arts. When she took the Associate Dean position over, the School was already operating at an overspend and despite it being balanced out half the time she was director, once the recession hit in 2009, she explained how the school became difficult to run.

“We shaved and paired down, made classes bigger, we did everything the rest of the university did but as the enrollments grew, and the allocation of our budget line didn’t necessarily grow with that,” Conaty said.

She explained that class enrollment in the School of Music and Dance as a factor to the overspending.

“Enrollment is growing at a faster pace than the university and because of that they have more majors than they used to, which is a sign that the recruitment efforts are paying off and that the school is attractive to students,” Conaty said.

The above charts show the Full-Time Equivalent Student (FTEs) numbers by semester from an undergraduate, graduate and post-baccalaureate perspective. Each graph starts at fall 2018 and goes back a decade until spring 2008. The undergraduate graph shows fairly steady numbers with a slight decline starting spring 2010 and gradually increased over the next 13 semesters until it shot back up and has been consistent since. Graduate FTEs have been on a decline since spring 2008 accounting for only about 33.2 FTEs for a semester. Post-baccalaureate graph shows peaks and valleys withe the highest accounted FTEs was in fall 2010 and the lowest in summer semesters. Overall, the School of Music and Dance receives significantly more FTEs from undergraduate students than it does with graduate and post-baccalaureate students. However, the total FTEs from across graduate levels is accounted for when calculating the final number.

In addition, the school has added to its general education offerings, especially in the online area, so more students across campus have access to music classes. These include classes focused on popular genres of music and ensemble classes such as symphonic band. Each of those classes are capped between 80 to 120 students, this generates more of FTES for the school.

“When they (colleges) exceed our targets, we get funding from academic affairs,” Conaty said. “If we don’t hit our targets, we get it pulled away.”

However, this isn’t the case for all classes with a higher cap on enrollment. If a one-unit class has 60 students, for instance, that’s only four FTEs, Conaty explained.

“If Music and Dance has a target of, say 500 FTEs, they would hit 500 FTEs each semester with their enrollments,” Conaty said.

When the financial crisis hit in 2009, Music Professor and current Arts Alive Co-Director Eric Smigel was tasked by then Director Conaty to create a general education class to get enrollment numbers up and to help possibly increase, or rather balance out, the school’s budget.

“She said ‘make it sexy,’ to appeal to the masses” Smigel said. “The School of Music and Dance is very expensive to run… so it needed to be balanced out with these large population classes.”

And thus, the Music 351: Psychedelic Rock of the 1960s class was born. It quickly turned into one of the most popular upper general education classes along with the hip hop class with enrollment reaching upwards of 100 students per semester, according to Smigel. In addition to the music of the 1960s, Music 351 expanded into various genres including disco music videos, Motown and hip hop.

“We need to balance out those classes that don’t generate great FTES,” Conaty said. “They have to have these big classes like hip hop or the psychedelic rock class, it’s vital.”

The addition of the class helped boost enrollment in classes within the School of Music and Dance but didn’t necessarily solve the budget issues entirely.

“The School has been exceeding its targets by and large, they’ve been getting rewarded and their budget has grown,” Conaty said “At the same time we’re trying to figure out how did it grow so quickly, the gap between the allocation and what they spent, where are those expanded costs?”

A way that the School of Music and Dance cut costs is through performing at venues at a discounted rate, performing under the dome of the Love Library or other locations around campus.

THE SHOW MUST GO ON

SDSU Live Downtown is an event that the School of Music and Dance holds every two years. Around 250 students in the school’s top ensembles and choirs perform pieces from various composers in one of San Diego’s most renowned music venues, Copley Symphony Hall.

It’s considered a highlight for students who participate at the bi-yearly event, Kitelinger says. It’s also almost completely donor funded.

During its first year, the concert received a Student Success Fee (SSF) from Academic Affairs, which aims to “enhance student success through expanded Academic Related Programs,” according to the SDSU Provost Website. However for its second performance, the school did not receive the SSF, which made funding for the concert difficult until a donor stepped in.

“We were fortunate that the donor stepped forward once they found out that that student success fee wasn’t there,” Kitelinger said. “They (the donor) said ‘oh, we’ll cover the cost’ because they really believed in it.”

Because of the partnership between the School of Music and Dance and Copley Symphony Hall, the School gets a major discount on renting the venue and a lot of the fees are waived, according to Kitelinger. However, the school is required to pay union fees and the cost of the online ticketing system the venue uses.

“We don’t pay what a normal group coming into the space would pay,” Kitelinger said. “We pay far less.”

Alex Ciavarelli practices his solo with the Jazz Ensemble in the Smith Recital Hall before a concert. Photo by Angelica Wallingford

The jazz ensemble, led by Bill Yeager, is one of those groups that filed successful Student Success Fee applications for its upcoming trip to Montenegro and for a 2016 album entitled “Jazztecs with Charles McPherson.”

“We had to go into it knowing that a lot of people weren’t really going to know the value of it because like half the people in the department don’t understand the value of it anyway,” Joyce said about the upcoming trip.

For the upcoming Montenegro trip, Joyce wrote the application. He explained that this wasn’t the first time that the Jazz Ensemble applied for funding to play in another country. They applied for a trip to Germany in 2017 and were unsuccessful.

According to Joyce, the biggest difference between the Montenegro and Germany trip is that the Montenegro government is sponsoring a lot of stuff for the ensemble while they had to account for every little detail for the German trip – and it added up quickly.

Joyce had to account for every last detail including plane tickets, transportation, hotel costs, luggage check, international charter busses, figure out how many students per room, the number of faculty attending as well as how much money per student the trip would ultimately cost.

Another concert, Symphony by the Sea, is held every fall in Imperial Beach. Thousands of people come to see San Diego State’s orchestra and band ensembles perform beachside, complete with fully rigged microphone system and tent erected specifically for the event.

The cost? Absolutely nothing.

“It’s great for us because we get a great audience and there’s no cost for us,” Kitelinger said. “The grant through the Pier Authority pays for it as an arts moment for the city.”

Another location where both concerts and rehearsals take place is what is called “the Plaza,” located between the School of Music and dance building and the Don Powell Theater.

Student musicians play on the Plaza frequently, the latest concert was in late October

“It’s great because it gives you that music-in-the-park kind of feel,” Gamez said. “People bring their dogs, coffee or they set up lawn chairs… which is great, it’s good for the community but you know we just don’t do community concerts the entire year.”

This Plaza, the area right outside of the Smith Recital Hall, provides a good acoustic space for performances and is completely free, another way to cut costs for the department, Kitelinger explains.

“I do a concert every fall on the Plaza … which is actually a really nice acoustic space because our backdrop is the music building and the sound bounces off the Don Powell Theater,” Kitelinger said. “It (the sound) kind of swims in between the two buildings.”

Other ways of cutting costs for the department are by performing music already available in its music library, which is one of the biggest expenses in the band budget, according to Kitelinger.

LOOKING TOWARD THE FUTURE

For some, a big issue for the department isn’t the budget, it’s the much-needed renovations to the 50-year-old music building. This means starting with an acoustically sound performance space.

“We don’t have a good acoustic performance space,” Shannon Kitelinger, director of bands said. “The Don Powell Theater exists, and there are others like Smith Recital Hall but those are not spaces that are acoustically very well made for live ensemble performance like we do.”

The School of Music and Dance has two designated rehearsal spaces. All the ensembles share M-114 classroom while Rhapsody Hall is for primarily a choral room. Last spring, an acoustician was brought in to test not only the rehearsal spaces, but the Smith Recital Hall and the Don Powell Theatre as well.

“All of them came in at one second of reverb which is extremely low,” Kitelinger said. “As a matter of fact, when the acoustician finished it he immediately said ‘oh, that’s not at all desirable for an acoustic ensemble.’”

All the rooms tested came in at one second of reverb, which is considered extremely low for a rehearsal space.

Gamez says what’s known as the Arts Plaza is in need of a makeover, starting with a proper performing arts center.

“It’s not enough just to have great students, you know you have to have the facilities to house them and make people want to come here,” Gamez said. “What’s going to make San Diego State and its performing arts program stand out from other ones?”

Kitelinger says certain spaces on campus, like the Don Powell Theatre, are great for theater productions because the theater department can manipulate the sound to make voices sound clearer and enhance the showcase. As for the ensembles, he thinks it’s not made for musicians to utilize in a proper way.

“The bands and orchestras still do stuff which is pretty impressive and the level that they play at is just as impressive,” Kitelinger said. “We put on like over 200 events each year in the school of music so, our students are always performing, they are always active.”

Practicing in the Don Powell Theater isn’t a new concept for performance ensembles.

Before the semester starts, marching band hosts a band camp for the new semester. According to Gamez, the marching band uses the Theater as a practice space when the weather gets too hot to practice outside. Gamez said that one day this fall, however, the band couldn’t use it and had to play in the Smith Recital Hall.

“They were sardined on the stage,” Gamez said. “It’s not a tiny theater but it’s not meant to house marching band rehearsals and not even necessarily wind ensembles or orchestras; It’s good for recitals, jazz combos, something smaller scaled not 50 plus people.”

In addition to better spaces for ensembles to rehearse and perform in, Kitelinger would also like to see the building soundproofed.

“Can you hear that?” Kitelinger said as the sounds of saxophone filled the closed office. “He’s three offices away, keep listening, you can hear everything.”

Kitelinger explained that you could hear everything going on inside and outside the building. When he’s trying to teach or advise, there’s always music being played or songs being sung. He cites the lack of soundproofed rooms as a source of frustration for non-music classes held in the building.

“Teachers and professors sometimes get really frustrated because there is music going on,” Kitelinger recalled. “We had one professor complain because there’s a piano in one of the lecture rooms, well it’s the music building we do use these classrooms for music as well so that could be frustrating because it’s not sound proofed in that sense.”

Along with soundproofing the decades old building, the entry of new degrees is something that could be up for discussion.

According to Conaty, she wants to see the School’s faculty to explore and examine a growing job market – neuroscience and music therapy.

“I think there’s an opportunity to examine whether a music therapy degree is a viable degree track in southern California,” she said. “Because there’s so few… degree programs offering that in California. It’s much more common back East.”

When she was director for the School, Conaty started the conversation of a potential music therapy program in 2009 but when the recession hit, it was placed on the backburner when her focus had to be on the programs current in place.

“We have a huge medical infrastructure here in San Diego that’s quite unique with Sharp and Scripps and UCSD’s center… Kaiser Permanente, I mean big medical infrastructure,” Conaty said. “I think there is a market demand, there’s certainly a job market for music therapists in allied healthcare field.”

Conaty also wants to expand the music entrepreneurship program to allow students who want a Bachelors of Arts and entrepreneurial experience without having it be performance based, like so much of the curriculum at the school is.

“There’s a performance aspect to it (Bachelors of Music) and a musicianship you have to have,” she said. “Maybe the BA (bachelors of Arts) degree can create opportunities for students who are more interested other genres of music besides classical and jazz.”

There’s also just general changes Conaty hopes to see, like inclusions of other genres, such as rock guitar, and different styles of classes in the curriculum to adapt to the changing music industry.

“We teach musical theatre, we teach classical singing, we don’t teach songwriting, we don’t teach things that are more music industry approach, the commercial style of music, those might be things we want to look at,” she said.

IN THE CODA

While Lipscomb is still learning his way around how San Diego State’s School of Music and Dance is run, he has high hopes for what the School can accomplish and maintains his belief that the arts, no matter the discipline, have a place amongst the science, technology and engineering subjects that is currently the emphasis of educators.

“Many of us have been trying to change it from STEM to STEAM to include the arts,” Lipscomb said. “The arts are vital and what they teach goes beyond just learning and instrument and reading notes.”

With the SDSU West initiative passing on Nov. 6, Gamez hopes that construction of a performing arts space is included in the expansion of the campus, which she says would give recruitment a big boost.

“You’re going to see numbers just bellowing over the next few years because of the new facilities that are going to get built, that are planning to get built, especially with the new stadium,” Gamez said. “I don’t see why a performing arts center is too far off the mark.”

In a perfect world, Kitelinger, Friedrichs and Conaty say that they would love to find a solution to the overspending that has been haunting the school for years. While all of them have their own way of dealing with funding, one thing resonates with them all: the students and wanting to focus on giving them the best experience and music or dance education possible.

“Because (when) I think of the best music, the best music is that which speaks to people and moves them and is relevant and virtuosity, excellence is the key,” Conaty said. “I want that to be visible and for people to see the process and the process itself gives meaning. When you share it, it can never be replicated.”